By Rob Krott

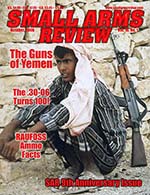

Its society beset by civil wars in the last fifty years, Yemen is awash in small arms. Nearly every Yemeni male over the age of ten carries some form of weapon, from the traditional jambiya (curved dagger) to assault rifles, as personal apparel and icons of masculinity. In the remote mountains and wadis, open carry of an assault rifle is not only common and widely accepted, but is considered de rigueur. Even heavy weapons such as the DsHk 12.7 machine guns and RPG-7s are available and they frequently crop up in inter-tribal clashes.

Yemen has a public weapons culture: weapons are openly carried, displayed, and fired in public. Every tribesman excepting the poorest owns a rifle (many have more than one) and in public each carries his rifle with him. The open and public carry of weapons is central to Yemeni male identity especially among Yemen’s tribal groups. Yemeni tribal society is completely male dominated and highly chauvinistic. Weapons are more than instruments of defense, hunting, and offense; they are also status symbols and visible proof of social standing. The average Yemeni male sees weapons as symbols of status, power, responsibility, manhood, and wealth.

Honor - sharaf - is a vital value in Yemeni tribal life and a weapon, especially the jambiya, is its symbol. These edged weapons are a highly visible mark of a tribesmen’s social standing. The most expensive jambiyas have handles of carved rhino horn and sheaths of worked silver. Traditionally, possession of “long guns” is limited to Yemenis with tribal affiliations. Non-tribal people living in tribal territories are not permitted to carry rifles, although many now own less ostentatious pistols. Furthermore, “men of learning,” although permitted to carry rifles, seldom do so and imams and tribal sheikhs seldom carry a rifle - but their heavily armed bodyguards communicate their status.

The 50 Million Guns Myth

Yemen reputedly has the highest per capita holdings of small arms in the world. The Yemen Ministry of Interior estimates there are approximately 50 million weapons in a nation of about 18 million.

This estimate has been widely reported in sources as disparate as The Economist, Reuters, The Associated Press, The Yemen Times, and The Lonely Planet Travel Guide. It is so embedded in the conventional wisdom and ‘mystique’ about Yemen that it is usually mentioned in almost anything written about the country. It is an incorrect and exaggerated estimate because, if it’s true, then every Yemeni male over fifteen years old owns more than a dozen guns. This apocryphal figure has never been revised and its origin is unknown, though it was already in circulation as early as 1990. Despite its fallacy, the number is something of a source of national pride for Yemeni tribesmen, but even they know 50 million seems rather high. Government officials and tribesmen alike nod, shrug, and sometimes smile when telling foreigners that their country is home to some 50 million small arms, the majority of which are fully automatic assault rifles.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs now provides an estimate of 15-16 million weapons and has estimated Yemen’s population at a little over 17 million. Removing 25 per cent of the population that was under 18 years old from this estimated population leaves about 6.25 million men able (under cultural practice) to possess arms.

But not every Yemeni man carries or owns a firearm. While the tribes in the north and northeast have a majority of gun ownership, lesser numbers of Yemenis in the major cities, coastal areas, central highlands, and “the south” own or carry firearms (an exception being tribes in remote areas, such as the Hawdramawt). Yemen probably has around 3.5 to 4 million gun owners. Even with an estimate of three firearms per gun owner there would only be 12 million publicly owned firearms. With a few million more equipping the military there might be about 15-16 million guns in Yemen.

Arms Smuggling and Gun Control

The Yemeni-Saudi border is a rugged mountainous area and very difficult to control and police. Border demarcation between the two countries per the Jeddah Treaty is ongoing. Exacerbating the border tensions is the arms smuggling problem (from Yemen to Saudi Arabia). The increasing proliferation of small arms in Yemen is mostly due to Yemen’s inability to police its borders. Weapons smuggling also hinders efforts to stabilize the border and fight terrorism.

According to Major General Saleh Al-Santali of the Saudi Border Guard, in a year’s time border guards arrested 381,900 illegal entrants while thirty-six border guards were “killed in action.” In 2002, Saudi border guards confiscated 263 firearms, 1.2 million rounds of ammunition, 47,600 sticks of dynamite, and large quantities of detonators along their porous 1,800 km long border with Yemen. In one instance, Saudi border guards stopped Yemeni arms smugglers with a load of grenades and automatic weapons intended for possible terrorist actions. That same day border guards in Jizan province engaged Yemeni gunrunners in a firefight, seizing 15 grenades and 10 pen-guns - coveted items in the Middle East for assassinations.

In August 2003 while I was working in Yemen, the Interior Ministry took serious steps to implement new procedures aimed at enhancing the efforts of security authorities in eliminating weapons possession and sale in the country. Strict orders to tighten control over weapons and explosives possession and even “fireworks” were sent out to security authorities in all governorates countrywide: those found selling weapons would face serious legal measures. Orders were given to confiscate all fireworks in the market and take shopkeepers to trial. Legal measures would be taken against those opening fire while celebrating weddings or similar occasions (celebratory gunfire is common in many areas of the Middle East.) Previously, prosecution for unregistered weapons has been limited to non-tribal areas in the South.

The new law probably won’t have much impact on the average Yemeni gun-owner: tribal life-ways and customs which govern weapons possession, use, and the consequences of use hold more sway than governmental laws; especially when weapons were still being openly sold and traded without government interference.

The Gun Markets

Firearms are readily available for sale throughout the country. Yemen has five major regional arms markets: Jehannah (in Sana’a governorate), Sadah, Al Baydah, Al Jowf, and Abyan. Except for Abyan, all are located in the north. There are about 300 gun shops in Yemen averaging about 100 weapons each. Many other small shops dealing in antiquities, jambiya, and jewelry also carry a small selection of antique weapons and serviceable firearms.

Talking with some American oil field workers I learned that some of them had bought Sniders and Martini-Henris in Sana’a and shipped them back to the United States without any trouble. I didn’t have the time to go to the arms market and look for antique weapons so I had to limit my hunt to the shops of the silver souk in Sana’a, which cater to expats and the odd tourist.

There I found at least a dozen shops with a few old bolt actions and muzzle-loading jezails in corners gathering dust, but I found only a few good quality weapons worth looking at and invariably the asking price was higher than what I could buy one for in the U.S. There were a few bargains though. Besides a C96 Mauser pistol, I inspected two pristine, nearly mint, German World War I era Lugers. Asking price was $300.

Cost, in Yemen to a Yemeni, is relative. While a Kalashnikov may cost about $180 in Yemen, $250 in Pakistan, and about $300 to $400 (for a semi-automatic version) in the United States, it is still a very expensive item to the Yemeni. That’s because the GDP per capita in Yemen is $820 a year, $2,000 in Pakistan, $36,200 in the U.S. The average Yemeni shells out almost 22 per cent of his annual income for a Kalashnikov, a Pakistani pays 12.5 per cent, and the average American gun-buyer is only out 0.8 per cent of his yearly income. Thus, for an average Yemeni, guns still aren’t cheap.

Arming Yemen

Yemen has not produced small arms since the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, so all weapons currently in use are imports. In recent years Yemen has received small arms from countries such as Argentina, Brazil, China, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, the Philippines, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, and the United States. Yemen then supplies black market imported arms to much of the Horn of Africa: including Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan. The importation of weapons into Yemen is nearly as old as the country itself. Among the earliest weapons known in Yemen were a pike and a sword that came from Asia, probably India, during the first centuries. Importation of small arms is closely tied to Yemen’s colonial past and its occupiers. There were three initial sources of weapons in Yemen: colonial presence, major power rivalry, and trade.

When the first Europeans arrived in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries they found that both the Turks and the Imam of Yemen had artillery installed in fortifications to protect themselves. In the third-quarter of the sixteenth century the Ottoman Turks brought in 2,500 harquebus guns. In the seventeenth century the Ottomans could mobilize forces of 8,000-10,000 men. Small armies of hardy Yemeni tribesmen well armed with muskets conducted several revolts and the Turks were eventually expelled.

By the eighteenth century, gun barrels and stocks as well as gunpowder were being manufactured and sold in Sana’a. In the nineteenth century, the possession of a matchlock was ordinary all across Arabia. One sheikh controlling a city and several villages could marshal an armed force of four thousand. Imports continued apace, so that visitors to Yemen in the early twentieth century could encounter tribesmen bearing matchlocks alongside others with bolt-action breech-loading rifles. The best Arab matchlocks remained in use until quite recently. Some of these had barrels made in British India.

In the Hawdramawt (Yemen’s Death Valley - a rugged area of mountains and wadis - the name translates loosely as “Death is Here”) I encountered tribesmen armed with Kalashnikovs, bolt-action WWII Mausers and, yes, even serviceable matchlocks. I was presented one along with a powder horn and an antique jambiya. Some Yemenis prefer older, bolt action or semi-auto rifles for various reasons including price, range, accuracy, and symbolic value. Antique Turkish pieces and old military service rifles are supplemented, rather than replaced, by modern self-loading and automatic rifles. Downstairs in many houses, among the grain and the goats, are heavy weapons such as mortars, machine guns and even light artillery pieces.

Just as the Ottomans had introduced thousands of harquebuses in the sixteenth century, now the influx of modern weapons are rifles. While Lee Enfields and FN FALs are still widely used and are appreciated for their reliability and quality, and therefore kept, the actual number of British small arms introduced in this fashion to the Yemeni tribes is limited. British military weapons are not commonly found today.

Mausers and Mauser variations are among the most common weapons in Yemen. Some are in the hands of youths whose parents have acquired more modern weapons. As the owner’s first token of manhood they are often prized possessions. The Mausers in Yemen today are nearly all Ottoman Empire in origin and represent the continuous re-equipment of the Ottoman forces throughout their occupation of Yemen, though there is also a large number of World War II era German 98K Mausers fielded in Yemen. It’s possible these 98Ks were from captured stocks provided by the Soviets as aid in the 1960s. While visiting a Bedouin encampment in the Hawdramawt, I fired probably a half-dozen Mauser 98Ks over the course of three days in impromptu shooting competitions. All were well maintained and serviceable.

Although the French never had a major presence in Yemen the French Gras rifle and the modified Chassepot are common and are found in use in Yemen. Few other French weapons are found. I handled about a half-dozen serviceable Gras rifles in the Sana’a silver souk. Gras rifles were already present in large numbers and with adequate quantities of cartridges and bayonets in the 1930s when more were purchased from France and brought in by Aden’s British colonial administration that issued them to local tribal levies.

Chinese and Soviet Weaponry in the Civil War

Egypt, in 1956 under President Nasser, nationalized the Suez Canal leading to a war with France, Israel, and Britain. After the intervention of the United States, the canal re-opened to shipping, and the warring countries returned to their territories. Yemen was key to the southern control of the Suez and through the support of Nasser’s regime the Soviets were able to influence the future of Yemen.

In 1962, Muhammad al-Badr inherited control of North Yemen from his father, Imam Ahmad Yayha and a week later he was overthrown in a military coup led by Colonel Abdullah al-Sallal. Colonel al-Sallal declared the northern region the “Yemen Arab Republic” (known as “North Yemen”) and started a Yemeni civil war. The deposed imam’s “royalists” received aid from the Saudis and the British, while the “republicans” received support from Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, including Egyptian troops. Nasser and King Faisal of Saudi Arabia met in 1965 to halt the civil war yet clashes resumed in 1966.

The British relinquished control of Aden on 30 November 1967 and pulled out of the South and the Communist-oriented Republic of Yemen (known as “South Yemen”) was established. Because some southern sheikhs allied themselves against the new Communist government, thousands of southern Yemenis fled north, seeking refuge in the Yemen Arab Republic and Saudi Arabia. Raiding (a Yemeni tribal pastime) soon began from the north into the Communist south. The raiders, supported by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia (unhappy with a new and radical pro-Communist nation on his border), were armed with U.S. surplus weapons as early as 1968.

When the British withdrew from Aden the Soviets quickly filled the vacuum, pouring military aid into South Yemen. Aid also included a huge buildup as the Soviets began large construction around Aden to support the Soviet military bases. Soviet weapons were funneled via Egypt and then directly to Yemen. South Yemen remained in the Soviet sphere of influence until the end of the Cold War.

Chinese weapons were probably smuggled into Yemen from the unguarded Omani border to the northeast. The 1965 Dhofari rebellion in Oman received Chinese support: Chinese small arms were smuggled across the Yemeni border to the Dhofar rebels. The Soviets and the Chinese both supplied arms to the Omanis in the renamed PFLOAG - Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arab Gulf). In 1972, the Cubans started sending officers to train PFLOAG units in South Yemen.

With the end of the Cold War, South Yemen suffered the same fate as other Soviet client states. Military aid and infrastructure support ended. The lack of continuing support also contributed to the unification of the two Yemens on 22 May 1990 under President Saleh. In 1994 the country erupted again into full-scale civil war fought by the regular armies of each former state with tribal support on each side.

President Saleh’s army wasn’t up to the task of defeating the South’s Soviet-equipped military. He made a bargain with the tribes if they helped defeat the South and brought their own weapons as the North didn’t have sufficient stocks of small arms to equip them, they could loot the South and carry off the large stockpiles of Soviet weaponry. The 1994 civil war resulted in an even wider distribution of small arms throughout Yemen.

During the 1994 civil war President Saleh also recruited Afghan veterans from across the Arab world to wage another victorious jihad against the secular socialists of South Yemen. At its height, the Yemeni Islamist network had its own school system, its own ministries, and even its own governorates, including Hawdramawt, the bin Laden ancestral home. After the fall of the socialists in the south, the Islamists set about filling the void with their own quasi-Taliban rule, a situation that Yemen has had to rectify.

(Rob Krott, SAR’s Military Affairs Correspondent, has been deployed in Iraq as an “independent contractor” with private security companies since December 2003. Prior to that, he was employed in Yemen as the regional security advisor for a large North American oil corporation.)

This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V10N1 (October 2006) |

| SUBSCRIBER COMMENT AREA |

Comments have not been generated for this article.